Debug Faster Please..

My three friends and I have only 5 more hours to finish debugging our last and final OS project. We’ve been working on it for over 16 hours non stop and all we want is to get the last test case to pass. We take a moment to be meta about our situation. If each of us has our own “bug fixing” rate and we team up to tackle different parts of the project, is finishing realistic? Can we actually compute the expected time it’ll take us to complete the project?

First we have to figure out a realistic way to model this problem.

First off, how do we actually model the probability that I fix a bug as a function of time? If you watch anyone debug code, for some extended period of time it just looks like he or she is staring at the code, typing things in here and there and often complaining. But then at some instant they transition from being in this staring/ typing/ complaining state to being in the ‘bug fixed’ state. Essentially a bug isn’t fixed until the exact moment it is. Thus we need to figure out - how can we accurately model this probability of reaching the ‘fixed’ state as a function of time.

Then we know that each person likely has a different ‘bug fixing’ rate. Given that I’ve recorded the amound of time it took me to fix each of \(n\) bugs, how can I determine my most likely ‘bug fixing’ rate? Let’s let \(X\) be a random variable representing the amount of time it took me to fix each bug. Thus \(X_1 =\) time to fix bug 1, \(X_2 =\) time to fix bug 2, etc. We assume that each is completely independent of each other. Solving one issue doesn’t influence any of the other problems.

Ok so once we figure these parts out, we have the most likely rate a person has for fixing bugs and the probability they do as a function of time. If we work in teams, however, we have to take that into consideration as well. Say we determine that it’ll be most effective for 2 people to work on each part of the proejct and since we are on the last test case, there is one bug in each part. Thus the expected time to finish each part would be whoever on each team takes less time. Once again we assume that each person works on fixing up their part independently and they don’t work together. Thus, how can we compute the minimum time given two individual probability functions? Lastly the total amount of time it takes to fix the program would be whichever subteam takes longer to find their bug. So once we’ve found the times for each pair, how can we compute the expected maximum time between both of the teams? We’ve got to model it all.

Transition Probability as a Function of Time

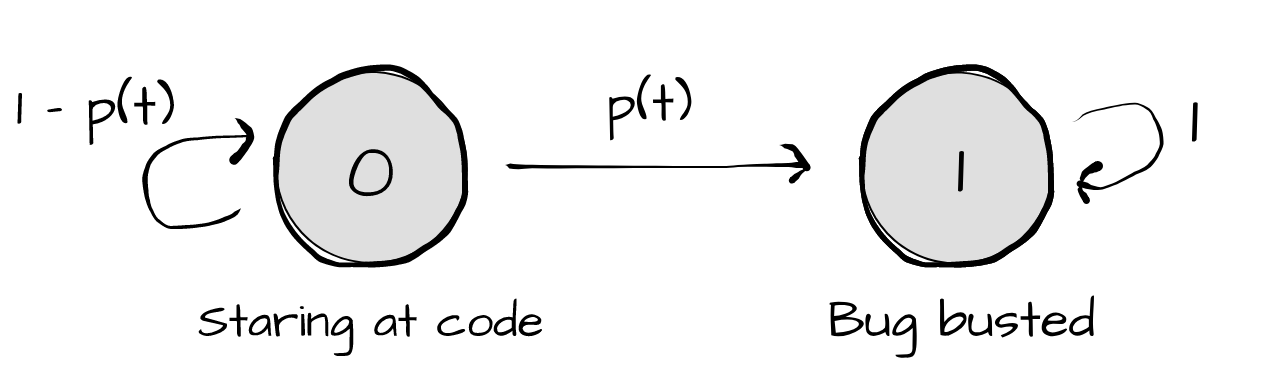

Ok let’s start by figuring out how to model the probability someone fixes a bug as a function of time. As with the previous problem we can draw a Markov Chain to represent this. It’ll have 2 states, one - ‘Staring at code’ and the other ‘Bug Fixed’. You have some function \(p(t)\) of transitioning to the fixed state and thus \(1 - p(t)\) of staying in the debugging state. Let’s draw out this Markov Chain.

Usually when we thinking of the probability that an event occurs we have it for a certain amount of time: P(eat 2 apples in a day), P(5 cars pass your house in an hour). Now however we want a rate, the probability for an instant in time. Thus we have a Continuous Time Markov Chain as opposed to the Discrete Time Markov Chain we were working with earlier. Looking to calculus, we can find the rate for this CTMC by taking the limit as this interval \(\delta t\) becomes infinitely small. This is the rate at which the probability distribution among states changes.

We can now simplify this equation. We remember from the discrete version that mutliplying by the transition matrix \(n+m\) times is the same as first multiplying by the transtition matrix \(n\) times followed by another \(m\) times. Essentially the Chapman Kolmogorov theorom states that \(P^{n+m} = P^nP^m\). The same holds here for the continous case \(P(t + \delta t) = P(t)P(\delta t)\) since you are computing the transition function for the same total amount of time. Thus we can pull \(P(t)\) out and we have

Since \(P(t)\) doesn’t depend on \(\delta t\) we have

Let’s represent this matrix of limits as \(Q\). Q still represents the transition matrix where \(Q[0][0]\) is the transition from state 0 to state 0, \(Q[0][1]\) is the transition from state 0 to state 1 and so on. The only difference is that in the continuous case you want to take the limit as the time interval for this transition probability becomes infinitely small.

We can now let the rate \(\lambda = \lim_{\delta t \to 0} p(\delta t)\).

Thus after performing the matrix multiplication we have the following differential equations:

Solving the differential equation for \(P(t)\) gives you \(P(t) = \lambda e^{-\lambda t}\). This represents the probability as a function of time that you transition from state 0 of debugging to state 1 of solving the issue. Thus we can model the waiting time until the first event occurs as an exponential distribution with parameter \(\lambda\)!

Most Likely Debugging Rate

Now, let’s figure out how to best estimate the rate \(\lambda\). Let’s say I wanted to find the estimate with the maximum likelihood of being the right rate. I record down the times it takes to solve each bug \(X_1, X_2, X_n\). Based on these times I want to find \(\lambda\).

To find the most likely value for lambda we differentiate, set it equal to 0 and solve for the maximum. We leave the ensuing math to the reader - this leaves us with

Time Taken per Pair

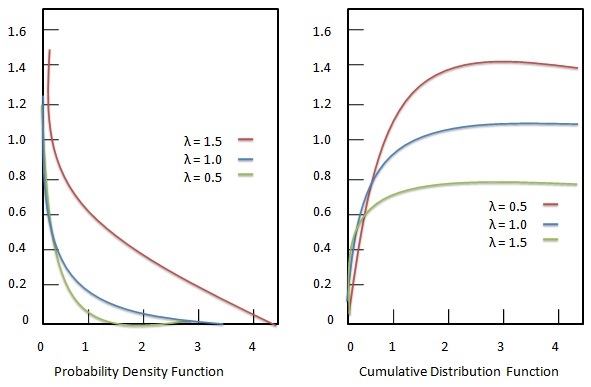

Now given each of our individual probability functions, let’s compute the minimum time when we both work on the same problem! In order for there to be a minimum to both of the exponential functions we can state that both functions must take on values greater than some constant \(a\). Let \(Z\) represent the random variable of the minimum of both functions. How do we compute \(P(X>a)\)? We simply need to integrate the probability density function for the exponential function from \(a\) to \(\infty\). Or we know that \(P(X < a)\) represents the cumulative density function which for the exponential function is \(P(X < a) = 1 - e^{-\lambda a}\) and thus \(P(X >= a) = 1 - P(X < a)\) and \(P(X >= a) = e^{-\lambda a}\) Thus \(P(Z > a) = (e^{-\lambda_1 a})(e^{-\lambda_2 a})\).

The following graphs show both the pdf and cdf of the exponential distribution.

Expected Total Time

Each of the pairs finish debugging their respective parts, now for the last step, figuring out the expected total time. This is simply the expected time of which group took longer.

Let’s compute the expected value of the maximum of two exponential functions!

Just like with the minimum of exponential functions we want to state there is some constant \(b\) which serves as an upper bound for both of the functions. Let W represent the max of the min of both pairs.

Now lastly we need to compute the expected value of the max of both of these variables. We can use one final trick to compute the expected value

\[E(X) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} xf(x) dx = \int_{0}^{\infty} (1 - F_x(X))dx\]This property is easier for us to use because we don’t have to differentiate and compute the pdf of our function. Thus our final expression states

\[\begin{align} E(max(Z, W)) &= \int_{0}^{\infty} (1 - F_x(X))dx\\ &= \int_{0}^{\infty} (1 - (1 - e^{-a(\lambda_1 + \lambda_2)})(1 - e^{-a(\lambda_3 + \lambda_4)}))dx\\ \end{align}\]Thus we’ve found the expected time for us to finish debugging our project!